Take a cursory glance at Soma, and you would see a sweet old lady with bird-like frailty and soft hair. However, a few seconds of observation tells us that something is not quite right: she is wandering in and out of her room, talking animatedly to the air in front of her, and seems to neither see nor hear us.

“She was such a superpower back then,” says Felicia Sallay, as we watch Soma. “She took care of my children as if they were her own, and my children doted on her. I feel so sad seeing her like this now.” At one point,Soma wanders upto us and holds her forehead. “They hit me”, she whimpers. “It hurts.” Then the next moment she is off again, muttering unintelligibly and walking aimlessly about. “This is normal,” Sallay explains. “She blabbers, sings, scolds and cries…at one moment she could be laughing, and then the next, she could be sobbing her heart out.”

Soma, 68, came into Sallay’s family about 25 years ago as nanny to her first child. She had remained with the family ever since, going on to take care of all her children. Sallay began to notice strange changes in her behaviour about seven years ago. “It all started after her father passed away,” Sallay tells us. “Soma loved him very much, so she was very sad about his death. But then she began coming to me saying odd things like ‘I had a long chat with my father today.’ I would tell her ‘There are no ghosts Soma,’ and drop it at that.” However, Sallay found her being increasingly absent-minded; she would serve the same curry in two separate dishes and leave jobs half done. “She would do these things, and then deny she ever did them,” she tells us.

Things came to a head when Sallay once noticed the curries frothing alarmingly on the stove. A tell-tale bottle of antiseptic sat close-by. Soma had added Dettol to the curries instead of oil. Alarmed, Sallay took her to see a doctor. The diagnosis: dementia due to Alzheimer’s.

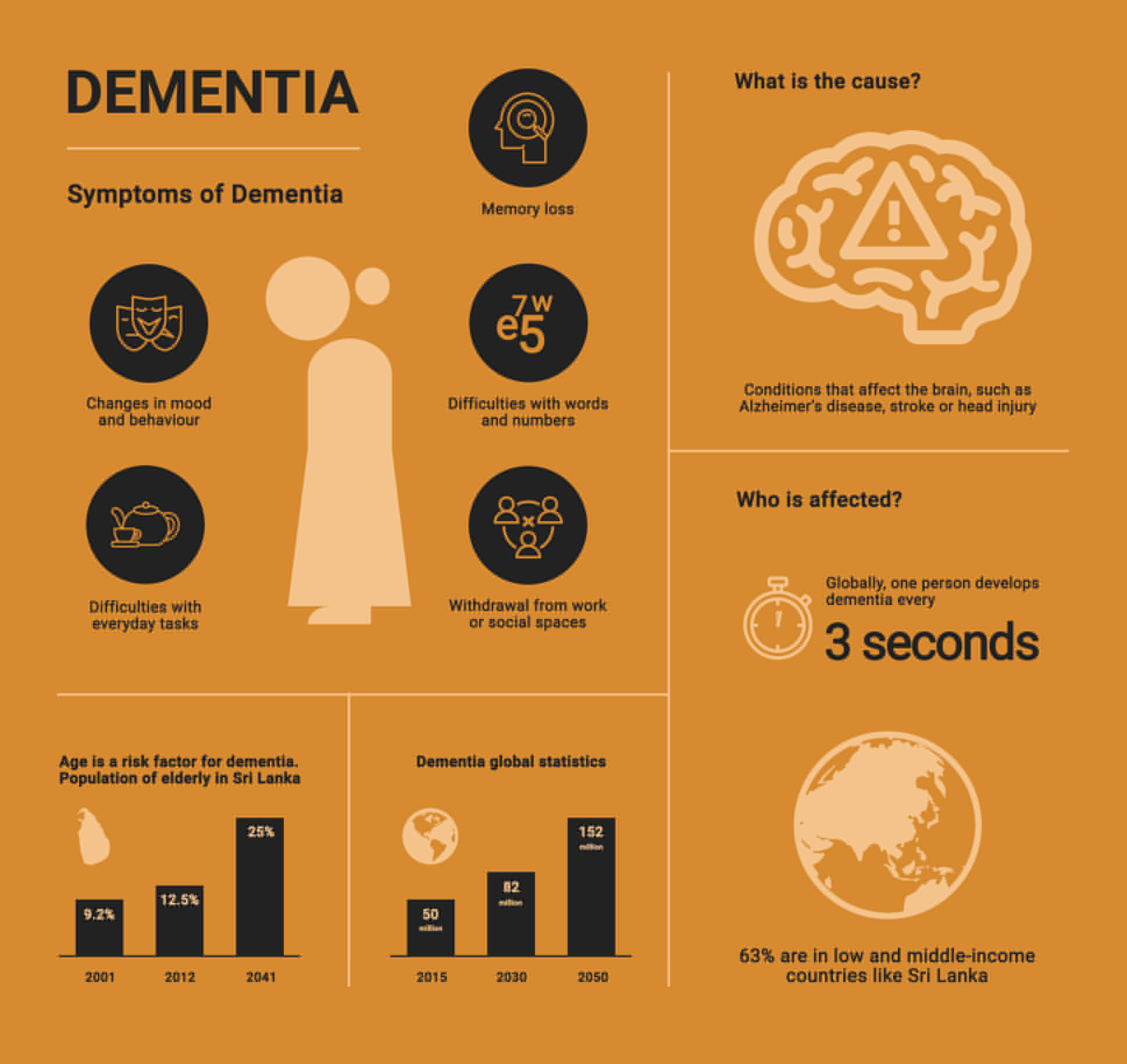

Soma is one of the 50 million people in the world who are currently living with dementia. We take a brief look at the disease’s human face in Sri Lanka; the urgent need for awareness in a rapidly ageing population, and most importantly, the impact it can have on the families and carers involved.

Dementia: A Snapshot

Picture waking up one morning with no memory of the face in front of you, the year you are living in, or even your own name. This is the terrifying reality of living with dementia.

Dementia is an umbrella term used to describe a decline in cognitive functioning like thinking, remembering, reasoning, and the ability to perform everyday activities. Apart from Alzheimer’s, dementia can be caused by other factors like a head injury, or a stroke. Its greatest risk factor is age, which is significant in Sri Lanka since the elderly population—that is, those above the age of 60—is rapidly escalating. Estimated to be 9.2% of the population in 2001 and 12.5% in 2012, that figure is expected to jump to a whopping 25% by the year 2041. About 5.3 million people in Sri Lanka will be over the age of 60 in 2041.

“Mostly, it all starts when people complain of forgetfulness,” says Dr Ruzaika Jaufer from the National Institute of Mental Health in Colombo. “They might wander around and forget where they are, forget names and faces, or find themselves repeating meals.” However, she also adds that many people dismiss forgetfulness as a normal part of ageing, and thus end up never getting diagnosed and treated. “Age is a risk factor, but this is not a normal part of ageing,” she says. .

Once diagnosed, there are certain drugs which are prescribed. Some of them, such as Donepezil, improve cognition, while others are sedatives to help patients sleep, or anti-psychotic drugs to treat symptoms like paranoid delusions. However, dementia is incurable. In its final stages, PWDs can reach a stage of complete inactivity and dependency. “After diagnosis, we usually send the patient home,” Dr. Jaufer explains. “We then educate the carers on how to manage the patient.”

Who Cares For The Carers?

Sallay’s clothes are wet when we visit her. “I was just bathing Soma, and she threw water all over me,” she laughs. “Even when I feed her, I sometimes end up with food all over my hair. Some days, she upends the plate all over the floor, or even spits the food on me.”

Soma has no family so to speak of; she left her home in the village when she was eight, and only stayed in touch with her father. The family in Colombo that she loved and grew up with have abandoned her – Sallay and her husband are all she has in the world. Sallay does everything from feeding and bathing her to taking her to the toilet and giving her medication – and the strain on her is incredible. “I have no help,” she says. “This is a full-time job. She can’t even remember how to swallow sometimes, so I have to literally tap her cheek after each mouthful until it goes down her throat. Someone has to always be in the house, so it is very difficult to go out.” Getting hold of help to take care of her is hard, she tells us, because this job requires an incredible amount of patience. The last dometic aide she got had lost her temper and ended up hitting Soma with a plate.

Sallay is not alone in her battle. It’s easy to forget the great economic, psychological and social burden of caring for a loved one day in and day out, with no respite. Many carers have other commitments as well, such as children and work, and it is often almost impossible to bear the weight of all these responsibilities.

“Most people only focus on the person with dementia,” says Lorraine Yu, the co-founder and president of Lanka Alzheimer’s Foundation (LAF). “Nobody thinks of the wife or the husband or the daughter who is the primary caregiver. You see, no one can do this 24/7 without help. They need some help from the extended family, the community, the neighbours, or even this foundation.” To date, she tells us that the country has no support system in place for the carers of dementia sufferers, apart from the LAF.

The Cost Of Dealing With Dementia

Mona Jayasuriya’s* (name changed) grandmother is in the later stages of dementia. The 88-year- old, who once single-handedly raised four children, is now bedridden and completely dependent on her family.

Her children pay Rs 35,000 every month for a carer to look after her. They were forced to get outside help because she would often get aggressive, screaming and raging and not recognising any of her loved ones. “The carer is not a trained nurse or anything, but she is very good, so we feel like it is worth it. This way, Aachchi gets the care she needs,” Mona tells us. “Homes are very expensive, and anyway, we like to keep her with us.” Other costs include medicines, consultant fees, hospital and ambulance charges, as well as peripheral costs like a special bed. Since they have hired help, the family members are now able to attend to their own day-to-day lives and fulfill other work and family commitments.

Sallay also admits that looking after Soma is hard on the purse strings. “The medicine is quite expensive,” she tells us, adding that institutional care is out of the question since she cannot afford it. “One of the homes I visited cost nearly Rs 150,000 a month,” she says. “Another cost Rs 100,000 a month.” However, Sallay has lost faith in institutional care – she once left Soma in a reputed home when she had to go on a trip abroad, only to return and find her tied up and beaten.

Caring for a dementia sufferer is often harder for people from low-income families. Dr. Jaufer tells us that the dementia ward in the NIMH has many patients who have been there for years. In most cases, their families cannot take care of them. “We are often quick to judge these people,” she tells us. “But most of them have no support system at home. For instance, if everyone in the family needs to work, how can they just leave the patient at home alone?”

Medication is given free in government hospitals on a monthly basis, but some drugs, like Donepezil are often unavailable and have to be purchased outside. “We try not to prescribe this drug since some individuals cannot afford it,” she says.

Lanka Alzheimer’s Foundation (LAF): Creating Dementia Friendly Communities

Tucked away in the heart of Maradana is a large airy building in an oasis of green. Inside it, a group of elderly people busily cut out paper flowers and sprinkle them with glitter. In one corner, two grey-haired men play carrom, while in another, an old lady takes a nap on a bed. A piano sits on a side. We would later hear the ‘clients’–Yu calls them clients, even though the services offered are free–lustily sing old classics like My Bonnie Lies Over The Ocean while a volunteer accompanied on the piano. A ‘cutting station’ is set up in the hall, where volunteers from a salon give the clients free massages, haircuts and manicures.

This is the Activity Centre of the LAF, a tranquil space created for PWDs to immerse themselves in a stimulating environment where they can enjoy music, crafts, cooking, gardening and other activities. It also gives carers a welcome day off from their responsibilities. One of the gentlemen playing carrom, Yaseen* (name changed), wanders over and has a long conversation with us about theology, world religions and tolerance. However, he does not remember his name when we ask him, and he has no idea where he is.

“If you met Yaseen in a supermarket, would you ever guess that he has dementia?” Yu asks. “This is their greatest disadvantage; their disability is not visible. This is why we need to create dementia- friendly communities.” According to Lorraine, one of the country’s greatest needs is to raise awareness and remove the stigma that surrounds dementia. “Everybody in the community should take the trouble to understand dementia and recognise its symptoms,” she explains. “If someone is repeating themselves many times, they are not doing it to annoy you. They are doing it because of their condition.” She describes how PWDs are frequently aware of their memory impairment, but are reluctant to accept this and get help. In most cases, they end up isolating themselves and hiding away from society. “If there is more awareness about dementia, there will be more support for PWDs and their carers,” she says.