Try as you may, the origins of the sarong ‒ also called a ṣārūn, lungi, fūṭah and so on depending on where in the world you’re from ‒ can’t be traced back to one particular country or region. From Malaysia to Indonesia, India and Yemen, several countries have, in the past, attempted to stake their claim to the garment, but the fact remains that the inhabitants of a significant number of places have been wearing sarongs, or versions of it, for as long as history remembers… and Sri Lanka is no exception.

Nobody quite knows when the garment first made an appearance on our shores, but records suggest that it rose to popularity during the British colonial era. In the book Costumes of Sri Lanka, it is said of the period: “the comfort of the sarong, loosely draped over the lower body… was, and still remains, the favoured clothing for home wear among men”.

Over the years, the sarong has grown into a wardrobe staple, with practically every man from a village farmer to the president himself having at least one hanging in their almirahs. It is the sarong’s ability to cut across social and ethnic divides, among other things, that makes it one of the most interesting pieces of clothing to be called our own.

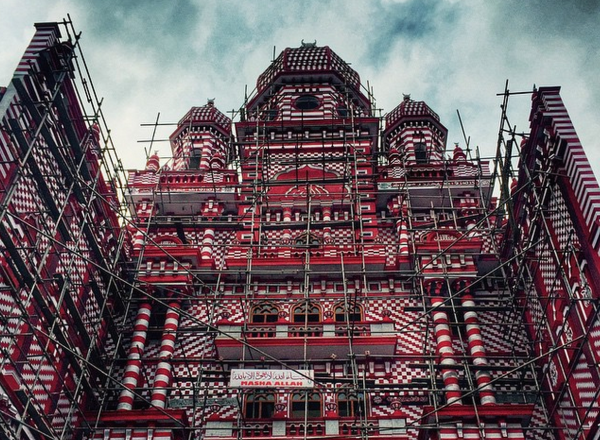

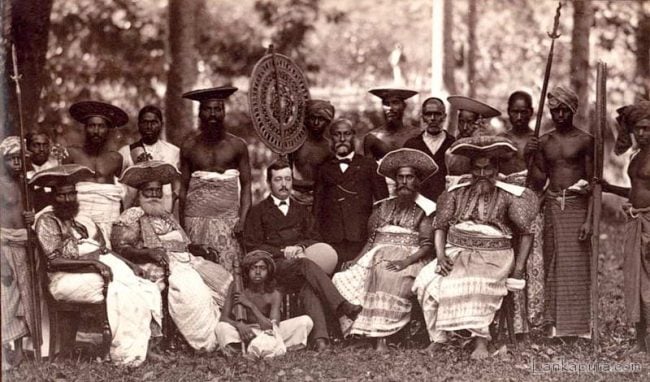

The Sarong Standstill

The sarong – worn by Sri Lankans of all walks of life, for generations. Image courtesy lankapura.com

In Sri Lanka, the form of the sarong has remained somewhat straightforward. It is, and always has been, a simple tube-shaped garment made to be tied at the waist, often incorporating the same traditional patterns and colours ‒ checks, stripes or batik, anyone?

The sarong’s inability to adapt to modern trends has led to a drop in its popularity over the past decade or so, with its role becoming confined, increasingly, to something to be worn when lazing around the house, to sleep or, at best, to a baila party.

Adding to the sarong’s sorry plight is the fact that it is frowned upon as being “informal” or “too casual” for the more exclusive establishments in Colombo. This may be the result of the stigma attached to the garment ‒ of its being attire reserved exclusively to the uneducated and those of the lower social classes.

Stigma aside, the general feeling amongst most people, particularly the younger generation, is that the sarong is “too much of a hassle” to be incorporated into their everyday lives. This sentiment is well portrayed in Sri Lankan YouTuber jehanr’s video about a new and improved version of the garment, which satirically highlights several of its downfalls.

Global Resurgence

Michael Kors is among the international designers to bring the sarong to the catwalk. Image courtesy Vogue

On the flip side, the West has always embraced the sarong as a statement piece, with Dorothy Lamour ‒ a singer and actress from Hollywood’s golden age ‒ being revered as “Sarong Queen” for her career-long affiliation with the garment, and David Beckham causing one of fashion’s biggest stirs when he famously wore the garment on a night out in 1998.

More recently, several fashion designers ‒ including big names such as Michael Kors ‒ have incorporated the garment into their spring/summer collections. This has inspired designers from countries in which the sarong is considered a traditional piece of clothing to feature it in their own collections. This was evident at Jakarta Fashion Week, where almost every menswear designer had at least one model walking down the runway in a sarong.

Closer to home, several big names in the local fashion industry have consistently produced the garment in scores, but have failed – at least until very recently – to market it as anything more than the traditional sarong. What’s more, little had been done, here or abroad, to enhance its functionality.

Spotting this opportunity to contribute to the global resurgence of the garment, Asanka de Mel – who was at the time working as a technology executive in Silicon Valley, San Francisco – set about creating a new and improved version of it, right here in Sri Lanka.

The Patent-pending Sarong

The LOVI sarong – complete with a much-needed pocket. Image courtesy writer.

When compared to the traditional Sri Lankan sarong – which usually employs no more than one line of stitching – the LOVI sarong appears to be a feat of engineering. The amount of technical thought that has gone into its creation is perhaps the reason that there is even a patent filed to protect its novel design.

According to LOVI, the addition of a pocket, and even the belt in lieu of the knot found on the traditional sarong, eliminates many of the difficulties presented by the garment in its traditional form, particularly those that hinder mobility.

In addition to providing some much-needed privacy, LOVI claims that the lining found on their sarong also works so as to break down the sweat induced by the Sri Lankan heat, making for a more comfortable experience.

In the aesthetic department, the Lovi sarongs break away from the traditional colours and prints found on sarongs in Sri Lanka and adopt a more modern, often monochrome, colour palette that is perhaps more attractive to the modern consumer than the more conventional alternatives.

While the sarong has been a wardrobe staple in the country for as long as anyone can remember, and the idea of a patent-protected sarong seems almost laughable the first time you hear it, it only takes one close look at the LOVI sarong to tell you why it is so ‒ it’s still a sarong, but one that makes noticeable improvements on the traditional version of the garment.

The Sarong Revival

Sarongs – the latest fashion statement? Image courtesy writer

With several brands, both local and international, embracing the sarong ‒ and LOVI going so far as to reinvent it and make it more functional ‒ the time seems ripe for the sarong to make a comeback.

Whether this means choosing to incorporate a sarong into your everyday wardrobe or merely trading your existing sarong in for a more state-of-the-art alternative, remains to be seen. But one thing’s certain – the sarong is back and it’s waiting on you to embrace it.

Featured image courtesy LOVI