A short series where we interview interesting personalities and put the spotlight on some of Sri Lanka’s intriguing professions.

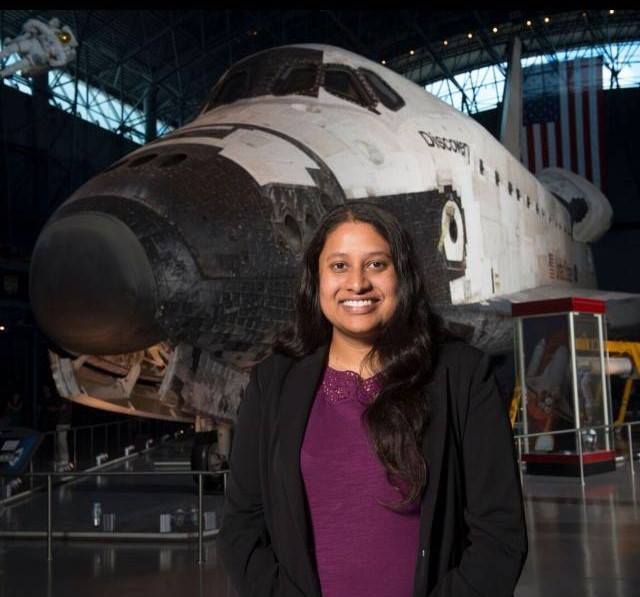

Hiruni Senarath Dassanayake is a young planetary scientist, based in and working from Sri Lanka. An avid follower of the National Geographic and Smithsonians, she has presented Mars mapping research at the Geological Society of America’s annual meeting in 2015. Dedicated to her career, Dassanayake states that her lifestyle revolves around the work she does. Here, she speaks to Roar Media about the unique work she does, and what it is like to be a female planetary scientist in Sri Lanka.

Hiruni Dassanayake

-

What made you interested in planetary sciences?

In Sri Lanka, being educated and successful usually means becoming a doctor, lawyer or an engineer. I wanted to break away from that tradition and become an adventure scientist! I have always been curious and driven by nature. Being a girl did not stop me from my adventure “planetary” scientist journey.

-

Who were your major influences and inspirations, and why?

My major influences and inspiration are my mentors. I learnt how to make decisions, navigate using my own compass and even learnt good values from them. I have worked very closely on my Mars research with my professor, planetary geologist Dr. Kevin Williams, and Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum (NASM) mentor Dr. John Grant. National Geographic Society’s Emerging Explorers Dr. Jeffrey Marlow and Dr. Asha de Vos have not only inspired me tremendously but also have given me great guidance, especially on my Global Mars project.

-

What was the most challenging thing you’ve done?

Embarking on my global educational/outreach project “Global Mars”.

Global Mars is an experience for students in traditionally under-served places in the world to engage in a unique education that would encourage them to pursue science and break the cycle of poverty.

We have created a dynamic planetary science-spark based curriculum and Sri Lanka is the first country in the world to pilot the program. The first part of the pilot already took place in August 2017 where we worked very closely with a government school in Matara, Sri Lanka. There are few educational programs that we are currently planning for 2018, as well as few fundraisers.

-

What are your working habits like?

These days I am very busy with my Global Mars project. When I am not doing Global Mars work, I spend a lot of time on my original research studying water related geology on Mars and its potential for life, using data from planetary missions that orbit planet Mars. Other planets and moons I have studied so far include Earth and Europa, where I used Arctic ice thickness and floe size to estimate ice thickness of Europa’s icy shell. Europa is an icy moon of Jupiter, that is thought to have a global ocean of water beneath its icy shell.

Other than that, I spend a lot of time brainstorming ideas, creating and bringing them to life. I also engage in mentoring, communicating science, teaching, travelling to conferences and I even do field work!

-

Is it easy being a planetary scientist in Sri Lanka?

No! Being a young female planetary scientist in the developing world is challenging, not only in terms of resources but also in terms of equity, opportunity and exposure. It is very challenging, especially in a country like Sri Lanka, where planetary science is not a very popular field of science. I am the only planetary scientist based in Sri Lanka with my specific research and education/outreach interest.

Cover image courtesy: nationalgeographic.com

Images courtesy of Hiruni Senarath Dassanayake