.jpg?w=1200)

Going by statistics alone, Sri Lanka is among the least urbanised countries in the world. According to the last census, taken in 2012, only 18.1% of the the country’s 20.4 million people live in cities, ranking the country 187th out of 194 in percentage of urban population. But numbers don’t tell the whole picture.

“This statistic underestimates the true urban population of Sri Lanka because of a definitional issue,” said Dr. Chanaka Talpahewa, Country Programme Manager for the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat). He was speaking at the launch of a report entitled ‘The State of Sri Lankan Cities 2018’, published in December 2018.

The report is the result of a comprehensive analysis of the nine provincial capitals of Sri Lanka—Anuradhapura, Badulla, Colombo, Galle, Jaffna, Kandy, Kurunegala, Ratnapura, and Trincomalee—with the aim of highlighting overall trends in urban development. Funded by the government of Australia, the research was carried out in close collaboration with the relevant local authorities and also had the support of the Ministry of Provincial Councils, Local Government and Sports.

“The misrepresentation of urban areas in Sri Lanka has resulted in the poor management of its cities,” said Benjamin Flower, coordinating editor of the project. “This report seeks to address that, by providing policymakers with up-to-date information about the state of cities, and recommendations of how to manage the various challenges they face.”

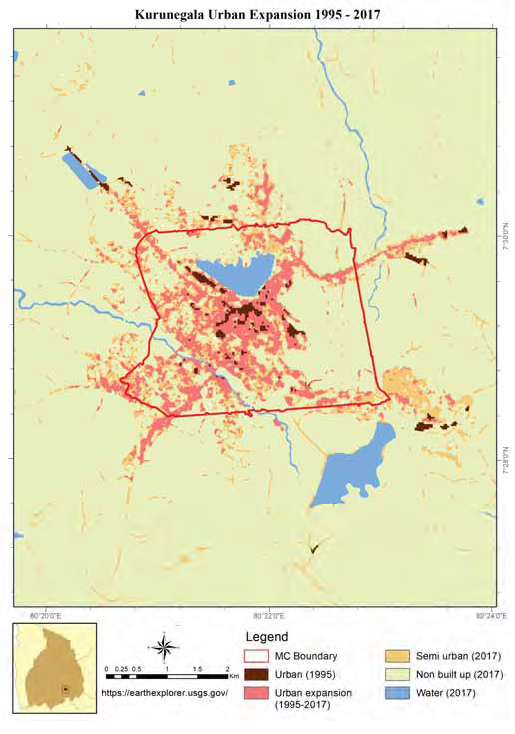

According to I. R. Bandara, Director-General of the Department of Census and Statistics, Sri Lanka’s urban population was previously measured using administrative and municipal boundaries. “But as the report shows, urban development has spread outside these boundaries.” In 1987, the country changed its urban boundaries by abolishing the unit of ‘town councils’, resulting in an overnight reduction in its urban population.

“Based on the criteria recommended by UN-Habitat, our new estimate, which takes into account features of the urban environment, places the urban population of Sri Lanka at 42%,” Bandara said.

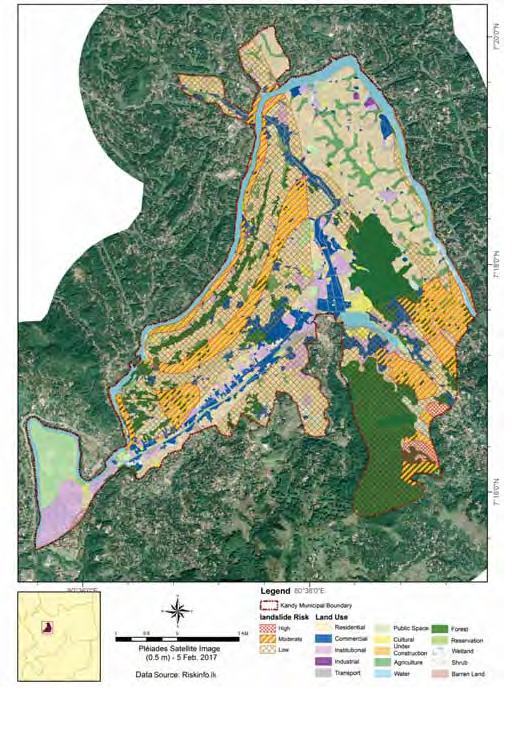

The study was guided by the UN Sustainable Development Goal 11, which aims to make cities inclusive (extend the opportunities of urban life across population sub-groups), safe (secure the personal safety and the health of their residents), resilient (adapt, recover and overcome shocks and stresses, including those associated with climate change, economic crisis and other disruptive events) and sustainable (sustain and develop over time without causing adverse effects to other urban processes and systems, such as ecological habitats).

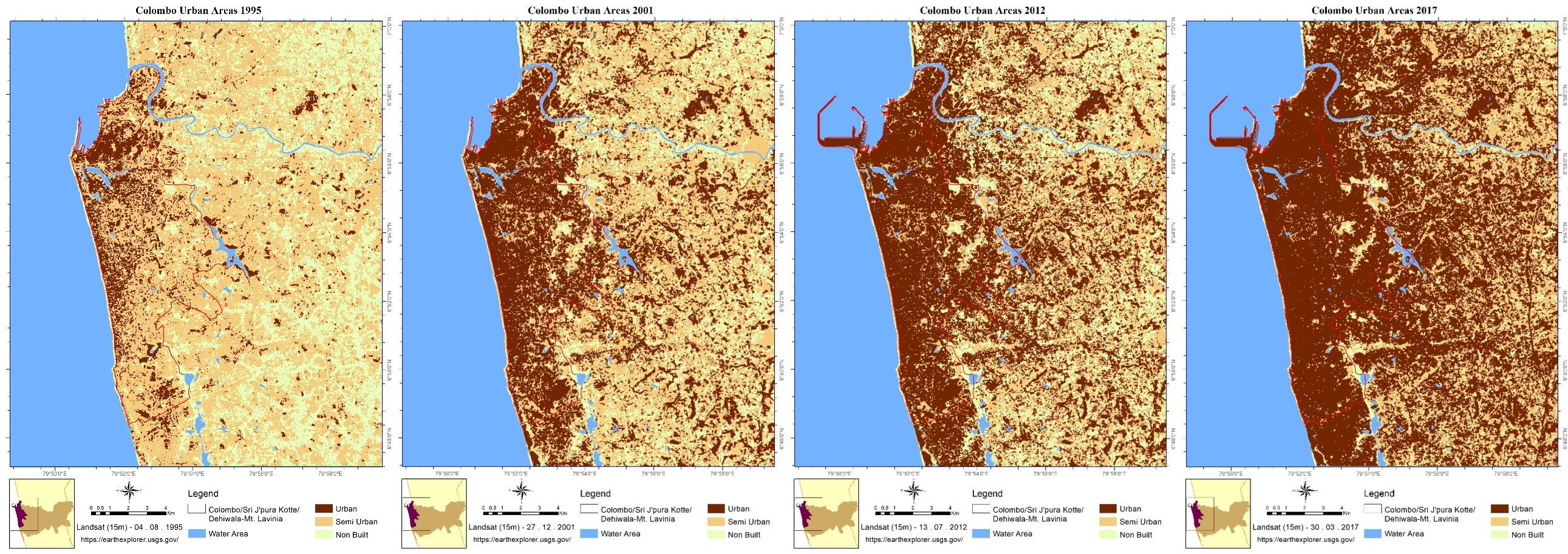

According to Flower, the underestimation of Sri Lanka’s urbanisation points to a larger issue — that of urban sprawl or the unregulated outward growth of a city outside its designated borders. “The urban spaces that are growing outside the city boundaries are unplanned and unregulated, and this can lead to a number of problems,” he said. Urban living in Colombo has become expensive as the city has developed and grown, fast becoming the exclusive city of high and low-income groups — the former able to afford high property prices, and the latter not minding living in slums as long as they are close to their place of work. Middle-income groups are leaving the city for the suburbs, where property prices are lower, but commuting to work in the city is still possible, placing a significant strain on the city’s transport systems.

This is one of the major issues with this low-density expansion — the increasing of commuter travel times, and the subsequent stress on infrastructure. While this may be seen as just an inconvenience, this phenomenon can have further consequences, such as increased urban mortality because of more road accidents, and higher air pollution. Colombo’s day-time population on weekdays is thrice that of its night-time population, with roughly a million people coming into the city to work. The public transport services are invariably over-crowded, forcing middle-income groups to obtain personal transport: usually motorbikes in the first instance and then cars. The travel speeds within the city have become as slow as 8 km/hr, if travelling by bus or car. Road widening and one-way flow systems have been implemented to some success, but continued growth will require more measures

Additionally, the report found that although women make up a little over 50% of urban population, they constitute less than 30% of the workforce. “While this may be because of traditional notions of women in the workplace, it may also be because of issues of safety on public transport,” said Faiszer Musthapha, Minister of Provincial Councils, Local Government and Sports, speaking at the report launch “There was a recent study that found 90% of women said they had been sexually harassed in public transport. Long commutes, especially late at night, may be discouraging women from taking jobs far from their homes.”

Urban sprawl also poses challenges when it comes to sustainability and resilience to climate change. “Colombo is a unique case, because of the heavy monsoon rains, and the fact that it is built amongst wetlands,” said Flower. “The wetlands play a significant role in mitigating the harmful effects of flooding.” However, as these wetlands shrink with more land being built on paved over, the capacity of the wetlands to hold flood water shrinks, and flooding in the city becomes a much greater risk.

The New Urban Agenda, promoted by the UN’s sustainable development goals, recommends the implementation of compact cities to combat various urban problems, and to raise the quality of life for city dwellers. With higher density, the most immediate benefit is the efficient provision of public services, such as garbage and sewage disposal, running water, and access to education, healthcare and safety services. This, in turn, will reduce vehicle usage, and shorten travel times, lowering the greenhouse emissions of the city as a whole. (On the contrary, the stress on infrastructure caused by low-density sprawl creates difficulties for local authorities in providing services to the city population.)

Reducing land consumption will also protect ecological environments on the periphery of cities, an issue most visible in Colombo, but present in all the provincial capitals. “The way to implement these measures is for the local authorities to put building restrictions in place,” Flower said. “But in Sri Lanka, these are poorly enforced as the local councils receive a tiny allocation of funds from the central government.”

However, it isn’t that compact cities aren’t a panacea to all urban problems. High-density cities have challenges of their own. For instance, Bandara mentioned that the Department of Census and Statistics still viewed cities “horizontally,” with the new “vertical” high-rises in Colombo prompting a reevaluation of their data collection methods. She further explained how Colombo’s garbage collection services had not fully adapted to the boom of high-rise apartments either. “The routes and allocations of garbage trucks still assume a relatively low-density city, where each area produces roughly the same amount of waste,” she said. “But one skyscraper can produce as much waste as a whole neighbourhood, and this needs to be considered.”

The growth of cities outside their municipal boundaries could be a reason for inefficient management. “What is essentially the same city now falls under multiple local authorities, and collaboration between them to provide basic services, like sewage systems for instance, can be rather cumbersome,” Flower said. Although UN-Habitat suggested a redrawing of the municipal borders, Minister Musthapha questioned whether this would solve the problem permanently. “In another 20 years, our cities may have grown outside these new borders, and they would have to again be redrawn, and then once again 20 years after that,” he said.

“This report identifies many issues and gives recommendations, but it is up to the local governments to implement them,” Flower said. “We have also created a trilingual database that will be online soon, with all the information we have collected. We plan to add more cities to the database, and hope that it will be consistently updated so it will be of use well into the future.”